Understanding Endometriosis

Current knowledge about this complex condition

What is Endometriosis?

Endometriosis is a chronic (pain) condition in which cells similar to those lining the uterus grow outside the uterus. This can occur in the pelvic region and remain localized, but can also spread to other areas such as the lungs or brain. These cells - wherever they are located - react to the hormones of the menstrual cycle and can therefore cause severe pain and many other symptoms.

Current Understanding (2026)

Endometriosis is today understood as a neuro-inflammatory whole-body disease associated with chronic inflammation and genetic factors. A 2023 study identified over 40 genetic variations that increase risk and showed connections to conditions like migraines, asthma, and other pain and inflammatory states.

Chronic pain in endometriosis can trigger central sensitization, which amplifies pain perception. This means the condition affects not just the reproductive system, but the entire body.

Key Facts

- Prevalence:Affects ~10% of women and people with uteruses worldwide (~190 million)

- Location:Can occur throughout the pelvis and beyond — including bowel, bladder, diaphragm, and rarely lungs or brain

- Diagnosis:Average diagnostic delay: 7–10 years from symptom onset

- Symptoms:Severity of symptoms does not correlate with extent of disease

Classification

Pelvic Endometriosis and its three subtypes

Endometriosis is not a uniform disease. There are three main subtypes of pelvic endo:

Ovarian Endometriosis

Often genetically predisposed and easier to detect on ultrasound. Forms cysts (endometriomas) on the ovaries.

Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis

Leads to persistent nodules deep in the pelvis, which can be visualized on MRI. Can affect bowel, bladder, and other organs.

Peritoneal Endometriosis

The most common form, yet hardest to diagnose as lesions are often superficial, transparent, and scattered across the peritoneum.

Did you know?

While endometriosis most commonly affects the pelvic region, it can appear in surprising locations throughout the body:

- - Lungs

- - Brain

- - Diaphragm

- - Eyes

- - Surgical scars

- - Sciatic nerve

These rare presentations highlight why endometriosis is sometimes called the 'chameleon of gynecology'.

How the disease behaves

Endometriosis is a remarkably heterogeneous, chronic inflammatory disease, traditionally characterized by the "presence of endometrium-like tissue outside the uterus", yet its clinical presentation varies widely—ranging from asymptomatic, "quiet" cases to severe, debilitating chronic pain and infertility. The progression and recurrence of endometriosis (e.g. after surgery) is notoriously unpredictable, with lesions exhibiting diverse behaviors and responses to hormonal and inflammatory cues, complicating both diagnosis and management. At the molecular level, dysregulated cell adhesion, aberrant angiogenesis, steroid‑dependent signaling, and altered immune and inflammatory responses together drive the multifaceted pathology of this disease. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for unraveling the enigmatic nature of endometriosis and developing targeted therapeutic strategies.

Disease Mechanisms

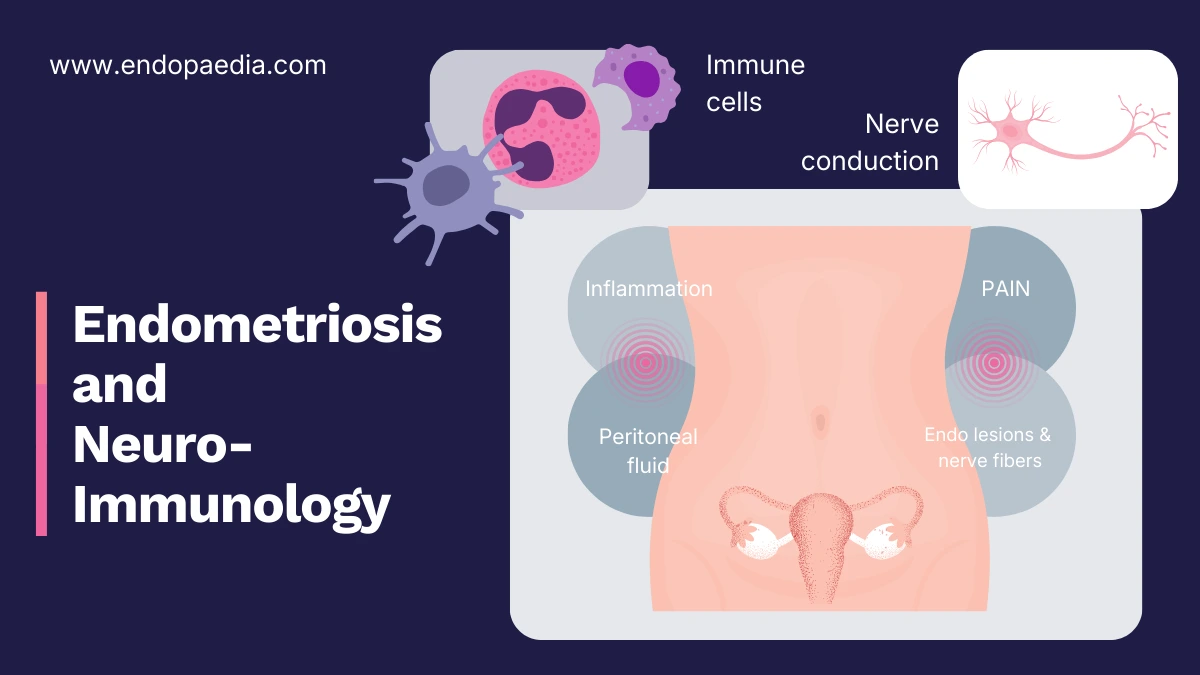

Neuro-immunological Background

The human body comprises complex systems that interact strongly. But which processes promote the development of endometriosis and its lesions and pain?

Natural Killer Cell Dysfunction

Although the number of NK cells may be normal, their function is reduced. This impairs the body's ability to clear ectopic endometrial lesions, promoting disease progression.

Immune-Nerve Interaction

Pain receptors (nociceptors) release the mediator CGRP, which activates macrophages via the RAMP1 pathway. Activated macrophages release pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-6 and TNF-α, further amplifying pain perception and creating a vicious cycle.

Persistent Inflammation

Endometriosis lesions evade the body's immune defenses and continue to grow. The resulting pro-inflammatory environment maintains pain signaling and promotes chronic symptoms.

Central Sensitization

Chronic peripheral inflammation leads to changes in the central nervous system, causing widespread pain similar to other neuro-immunological conditions.

Environmental Factors

Toxin exposure (such as dioxins) during the prenatal period may affect the development of the nervous, endocrine, and immune systems, potentially contributing to endometriosis later in life.

A better understanding of these immunological mechanisms is crucial for developing new therapeutic approaches that specifically target the pain and inflammatory components of endometriosis.

Origin Theories

Several theories attempt to explain how endometriosis develops. Research continues to uncover the complex interplay of genetics, immune function, and developmental biology.

For a comprehensive overview, see: The Main Theories on the Pathogenesis of Endometriosis

Embryological Theory

Müllerian Rest Theory

This theory proposes that during embryonic development, cells destined to become endometrial tissue are misplaced outside the uterus. These cells remain dormant until puberty, when hormonal changes activate them.

The video below presents Dr. David Redwine's explanation of the Opitz theory of embryonal mesoblast origin.

The original English video from January 29, 2021 can be found on Dr. David Redwine's (†2023) Facebook page. Facebook

Retrograde Menstruation

Sampson's Theory

This theory suggests that menstrual blood containing endometrial cells flows backward through the fallopian tubes into the pelvic cavity, where cells implant and grow.

While retrograde menstruation occurs in most women, only some develop endometriosis. This suggests additional factors - likely immune dysfunction - determine who develops the disease.

Detailed content coming soon

Associated Conditions

Endometriosis patients have significantly elevated risks for other conditions:

- -5x higher risk for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

- -2x higher risk for ADHD

- -Increased cardiovascular risk (15-35% higher risks of composite cardiovascular outcomes, ischaemic stroke, or myocardial infarction)

- -Depression and anxiety disorders

- -Rheumatoid arthritis and lupus

- -Asthma and allergies

- -Migraines

- -Fibromyalgia

Evidence for links with MCAS and POTS is currently limited and largely based on overlapping symptom profiles and small or anecdotal reports rather than large epidemiologic studies.

A large Swedish population-based study of over 800,000 women found strong links between endometriosis and psychiatric disorders. These associations cannot be fully explained by shared familial factors, highlighting the need for integrated psychosocial support. (Gao et al. 2020)

Endometriosis affects many body systems and should therefore not only be managed by gynecologists but also by general practitioners to avoid misdiagnosis and inadequate treatment.

Endometriosis in Women of Color

Detection, Disease Extent, and Statistics

This sneaky, chronic inflammatory disease unfortunately exhibits significant racial and ethnic disparities in diagnosis and disease presentation. Research also demonstrates that racialized pain perception (rooted in historical and ongoing biases within medicine) contributes to delayed or dismissed reports of pain among women of color, particularly Black women. Their pain is still partially underestimated compared to their White counterparts. A systematic literature review from 2019 showed that Black women are about 50% less likely to be diagnosed with endometriosis compared to White women, which does not mean that they do not suffer from it. These disparities are not fully explained by biological differences but are influenced by systemic biases, as well as socioeconomic factors and access to accurate healthcare. Furthermore, women of color are underrepresented in endometriosis research, comprising only a small fraction of participants in clinical trials, which limits the generalizability of findings and perpetuates gaps in understanding disease presentation across racial and ethnic groups. For example, 40% of African-American women with laparoscopic evidence of endometriosis were initially misdiagnosed with pelvic inflammatory disease, highlighting misconceptions and the dreaded diagnostic delay. Non-White women in rural areas are less likely to have access to minimally invasive surgical options and more likely to experience surgical complications, further exacerbating health inequities. Endometriosis being a disease of wealthy / industrialized women is a misconception that is gradually losing its hold – not least because of heroic factual reports and sad cases of extreme disease among women of color influencers.

Racial and ethnic minorities face unique challenges in endometriosis detection and management, underscoring the need for culturally competent care and further research into disease presentation across diverse populations.

Psychological Impact & Quality of Life

Pain and Psychology

There is no cure for endometriosis, but various treatment options can relieve symptoms. Treatment depends on how the disease manifests individually. But what should you know about the psychological effects?

Endometriosis is considered the most common and serious disease of women of reproductive age. It is estimated that over 170 million women worldwide suffer from endometriosis. The incidence continues to rise and is increasingly affecting younger women.

Clinical Manifestations

Chronic Pain Syndrome

Persistent pelvic pain that can significantly impact daily activities, work, and quality of life. Often worsens during menstruation but may occur throughout the cycle.

Infertility

Endometriosis is found in 30-50% of women experiencing infertility. It can affect egg quality, fallopian tube function, and implantation.

Dyspareunia

Pain during or after sexual intercourse, often described as deep pelvic pain. Can significantly impact intimate relationships and emotional wellbeing.

Psychosocial Impact

Endometriosis negatively affects general health, performance, and quality of life. Beyond the physical symptoms, it can disrupt psychosexual relationships and lead to changes in feminine and social roles. The main clinical manifestations - pain syndrome, infertility, and dyspareunia (painful intercourse) - along with the chronic, recurring nature of the disease, can act as strong psychotraumatic factors.

Chronic pain syndrome is one of the main manifestations of endometriosis and significantly limits quality of life. The pain can restrict activity and performance, and affect the emotional state, social life, and intimate relationships of those affected.

Surgical Staging

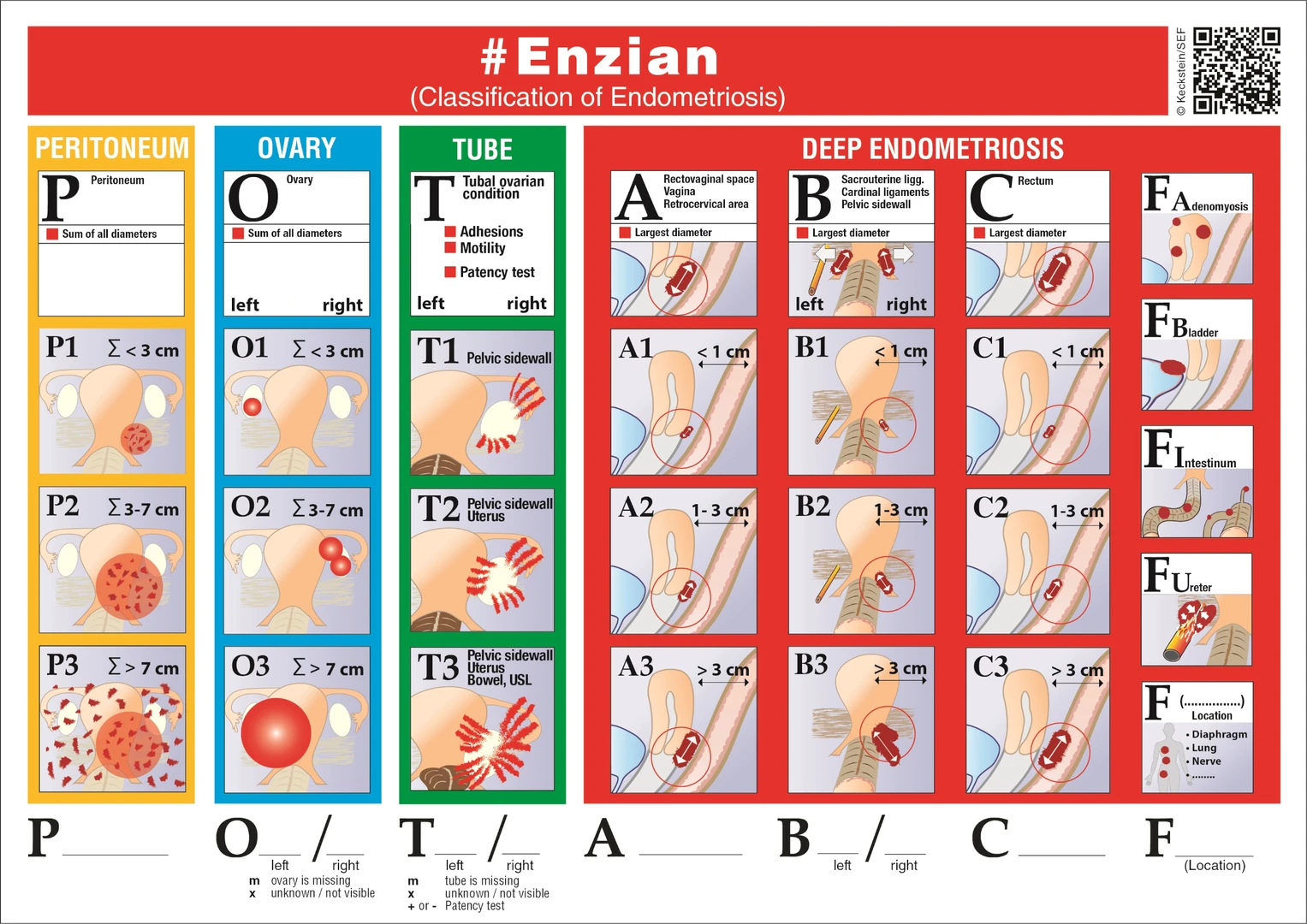

ENZIAN Classification

The ENZIAN system, developed by Dr. Keckstein and colleagues, has been used for several years to classify the severity and location of the disease. It provides a standardized way to describe the often confusing spread of lesions discovered during surgery.

"The #Enzian classification: A comprehensive non-invasive and surgical description system for endometriosis." Jörg Keckstein, Ertan Saridogan, Uwe A. Ulrich, Martin Sillem, Peter Oppelt, Karl W. Schweppe, Harald Krentel, Elisabeth Janschek, Caterina Exacoustos, Mario Malzoni, Michael Mueller, Horace Roman, George Condous, Axel Forman, Frank W. Jansen, Attila Bokor, Voicu Simedrea, Gernot Hudelist

View ENZIAN Classification Study

Frequently Asked Questions

Below are answers to the most common and most misunderstood questions about endometriosis.

Endometriosis is a chronic condition where tissue similar to the uterine lining grows outside the uterus, causing multiple symptoms, often including pain, fatigue, and sometimes fertility issues.

Common symptoms include chronic pelvic pain, pain after or during sex, fatigue, and digestive issues, though severity varies widely.

Genetics may increase risk, but environmental and hormonal factors also play a role. Family history can inform early awareness and monitoring.

Trusted sources include certified endometriosis centers in hospitals, patient advocacy groups, healthtech researchers (see Directory), trusted websites (see Links), endopaedia, and documentaries like nicht die regel that share lived experiences.

Yes, it can impact work, relationships, mental health, and physical activity, making awareness, support, and early intervention critical.

Treatments include pain management, hormonal therapies, surgery, and lifestyle strategies. Treatment is often personalized depending on symptoms and goals.

You can join local patient groups, attend screenings or talks, participate in awareness campaigns, or enrol in active clinical trials.

Yes, screenings, talks, podcasts, and research collaborations are available - contact me via the site to book a session.